Anyone who’s gone through strategic planning reviews at places of business under financial distress knows they’re often a prelude to redundancies. Too often, reviews look to see what might be cut, and what can be made of what is left, rather than building toward new opportunities.

Minister Mahuta’s review of the role and function of local councils is in similar position.

Local government has, for the past couple of decades, been treated like a hopeless child in constant need of direction, or correction, from its central government parent. Trusted with little, local councils have had difficulty in attracting talent and competence, creating self-perpetuating cycles.

Water infrastructure has been a core area of local government responsibility. It has not always gone well. Councils have not been keeping up with necessary investment to maintain existing networks, let alone provide for growth. Nikki Mandow reported on Water New Zealand statistics chronicling underinvestment in water assets. The median council, over the past three years, invested 70% as much as was necessary to keep up with depreciation in water supply, 53% as much as was necessary to maintain wastewater networks, and 15% of what was needed in stormwater.

So central government began the Three Waters Review to take water away from local councils.

The expropriation of billions of dollars of council assets has drawn some criticism from local council, but not nearly as much as might have been expected for the amount at stake.

Central government may be providing an offer councils cannot refuse. Where central government commissions estimates of up to $185 billion dollars in water infrastructure deficits, local government may well worry what the alternative to amalgamation might be. A council objecting to amalgamation might be told to meet centrally imposed standards requiring tens of billions of dollars in investment – and ratepayer revolt.

Consequently, the Three Waters Review has been proceeding as fait accompli. Water will be taken off councils. The main remaining questions are around the number of amalgamated entities that will hold those assets, whether it is possible to maintain joint council ownership of the amalgamated entities and the strict balance sheet separation necessary for financing water infrastructure, and the appropriate regulatory structures for the water bodies.

Left out of that discussion, and shifted to the Local Government Review, is the larger question of just what purpose local councils will serve, and will be able to serve, when they are stripped of a substantial part of their asset base and staffing.

For smaller councils, running a water utility means having staff around who can also help with general accounts and management of other parts of the operation. Stripping that out will hurt capabilities.

At the same time, Resource Management reform following the Randerson Review would shift a lot of Council planning functions from local government up to regional councils.

So, whither local council?

It will be a hard question to answer – or at least no one size will fit all. Some local councils may need to shift to shared service arrangements with neighbours to be able to continue operations. Others will be fine.

And the temptation in the review, as in other strategic planning reviews, will be to look for cost savings rather than new opportunities.

But opportunities do exist.

Subsidiarity means leaving decisions to the lowest level able to handle them, from individuals and families up to community groups, local government, regional government, central government and multinational agreements. If the costs and benefits of a government activity are confined to a local area, then local council should be the one to handle it, if they can handle it.

Approaches based in subsidiarity have a lot of advantages. Different things work in different places, and ratepayer preferences can vary across councils as well. Subsidiarity, as a principle, lets policy and practice vary from place to place in accordance with local circumstances.

But approaches based in subsidiarity have had a difficult time in New Zealand because central government has never really been able to trust local councils to manage anything important. Capability building then has to be an important part of any reframing and reshaping of the role of local council.

The local government review does not need to prescribe some new smaller size to fit all councils. It could instead provide a framework enabling local councils to carve out the paths that work best for their communities, in consultation with their communities, but with accountability for outcomes.

Devolution deals along the lines of those pioneered in Great Britain over the past decade could provide something of a model.

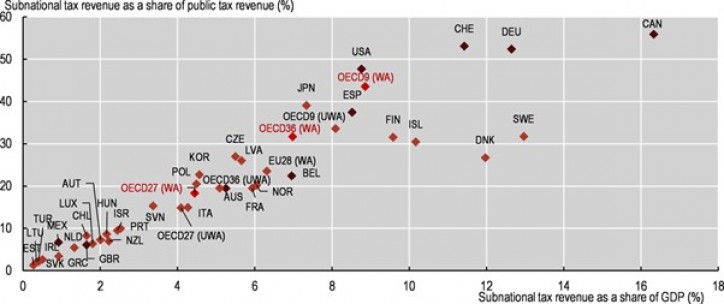

Like New Zealand, Britain has a very centralised system of government. Less than 10% of public tax revenue in both places goes to local or regional governments.

In 2014, councils in the Manchester area struck a deal with central government. Councils would receive devolved authority over local transport, new planning powers to encourage development, some authority over skills training, and an ‘earn back’ funding arrangement rewarding local councils if economic growth targets were achieved.

Since then, nine other councils have struck devolution deals.

Modified to suit New Zealand circumstances, these kinds of deals could provide the basis for a new kind of localism. Rather than central government telling local governments what they might be allowed to do, once water was taken off of them, local governments could make their pitch to central government for the things they’d like to be able to do, the devolved funding lines that would be needed to make it work, the metrics that would hold them accountable both to central government and to their communities, and the incentive framework ensuring that local and central governments shared in the resulting benefits.

In 2015, the Initiative released a report arguing for this kind of approach. We argued that councils should be able to make their cases, individually or as regional groupings, to Treasury. Officials would help to work through the accountability frameworks, while keeping an eye out for unintended consequences. If a devolved authority proved successful, other councils could apply for the same treatment. If it did not, the experiment could be wound back at lower cost than had it been rolled out across the whole country. And councils could learn from each other about the kinds of measures that worked, and those that did not.

The report provided a few examples of the kinds of deals we would have liked to have seen come of that kind of arrangement, but only as examples. Fundamental to the framework is that devolution proposals would need to come from councils themselves, in consultation with their communities, rather than from report authors sitting at desks in Wellington.

A large part of the problem facing councils in accommodating population growth has been that while the benefits of urban growth flow to central government’s coffers, the costs lie with councils. Incentive frameworks rewarding councils for doing things that improve central government’s tax take, sharing the benefits of growth, could square the circle while encouraging local government innovation.

With water infrastructure being taken from councils, councils and central government have to figure out what local councils’ remaining role might be. It could finally be an opportunity to steer away from having one model for all councils. We could build a framework enabling councils to grow in the ways that best suit their local communities’ needs, while ensuring necessary accountability.