Russia’s invasion of Ukraine combined with a global pandemic and a Reserve Bank that has forgotten its core inflation mandate do not make a case for cutting petrol excise and road user charges.

And yet, here we are. The government yesterday announced a temporary cut to petrol excise and to road user charges.

It is not a good idea.

Misunderstanding how petrol excise works has been part of the problem. But so too has been an inequity baked into petrol excise settings, and failure to compensate households for rising carbon costs.

Over the past week, it became rather obvious that a lot of people believe that the government earns more tax revenue when petrol prices are rising, making petrol taxes seem unfair.

But excise on petrol is a per-litre charge. The government does not earn more revenue just because petrol prices have increased.

In normal times, just over 70 cents from every litre of petrol goes into the National Land Transport Fund, which is meant to fund transport infrastructure.

The Accident Compensation Corporation gets six cents from every litre as part of the insurance premium paid by drivers.

The two together are equivalent to the Road User Charge on diesel vehicles. They do not go up when oil prices go up.

A bit more than half a cent per litre is charged as a fuel monitoring levy, and two-thirds of a cent per litre goes back to local authorities as a Local Authorities Fuel tax. All up, it’s just over $0.77 per litre – plus ten cents in Auckland due to their regional fuel tax. The Auckland Regional Fuel tax is meant to be funding Auckland transport infrastructure.

Petrol and diesel also carry a carbon charge. The fuel companies buy carbon credits in the Emissions Trading Scheme to cover the emissions when their fuel is used. Every litre of petrol comes with 2.45 kilograms of carbon credits. Carbon permits currently cost about $70/tonne, so the carbon charge is just over $0.17. And while carbon is a lot more expensive than it was five years ago, the price of carbon is about $10/tonne lower than it was earlier this year.

Rising carbon costs are part of the longer-term increase in fuel prices. The Emissions Trading Scheme is doing its job. But carbon charges have nothing to do with the current price surge. If anything, an oil price shock coming from Russia invading Ukraine should lead to reduced demand for carbon credits and push carbon prices down.

And while it is certainly true that 15% of a larger number is larger, so the government will be earning more in GST from spending on petrol, GST covers more than just petrol. New Zealand has about the world’s most comprehensive GST. So if people cut back spending elsewhere to deal with rising petrol prices, the government earns less GST on those other expenditures. Rising petrol prices are not a revenue-generator for the government.

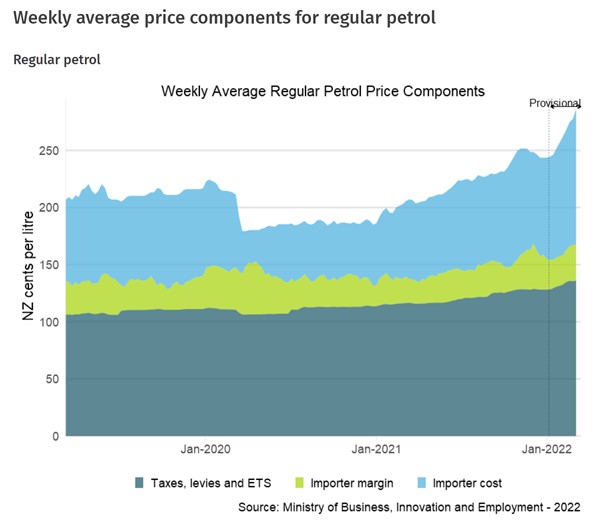

MBIE provides weekly updates that break down the cost of petrol. Unsurprisingly, the current price surge has nothing to do with excise, or GST, or carbon charges. The price of imported fuel has just increased.

Cutting excise, when global fuel supplies are constrained and supply chains are disrupted, would generally have less effect on final prices to consumers than anyone might hope.

A general principle of public finance holds that the side of the market that is less able to respond to price changes bears the larger part of the burden, or enjoys the greater part of the benefit, of a change in taxes. Burdens, and benefits, tend to be shared.

Or to put it another way, changes in excise would be unlikely to be passed through completely to consumers.

Normally, it would be safe to view fuel supply as relatively elastic for New Zealand, at least over a medium term. But we are now in a global oil supply shock.

During the press conference announcing the temporary cut to petrol excise, the Prime Minister warned that the government will be watching petrol prices and fuel company margins closely.

If it would be hard for petrol companies to increase supply in response to a drop in excise, they would wind up bidding up the price of fuel being imported. The retail price would drop by less than the amount of any reduction in excise – and the fuel companies then risk populist blame and government censure. I do not envy them the next few months.

Finally, both excise and road user charges are meant to cover the cost of the transport networks used by those paying those charges. There is no good reason to expect that the cost of road building and maintenance goes down when oil prices go up. If anything, it should be the opposite. Roads use bitumen, which derives from oil. Big yellow machines also use fuel.

Minister Robertson, during yesterday’s announcement, signalled that the government will top up the Land Transport Fund using general revenues.

All up, adjusting petrol excise when global oil prices change makes little sense. It would have made no sense to hike excise in response to very low oil prices at the beginning of the pandemic, and it makes no economic sense to reduce them in response to high current oil prices.

But that does not mean that the government should do nothing.

Carbon prices are not to blame for the current oil price shock. But we should expect carbon prices to rise as the government moves toward Net Zero. Carbon charges will impose a larger burden on household budgets.

And, unlike petrol excise, government will profit from rising carbon prices. The government intends to auction 19.3 million tonnes of carbon credits over the coming year – with more credits held in reserve in case the price cap is hit.

If the government can sell a tonne of carbon credits for $72, it will earn just under $1.4 billion through this year’s auctions.

Currently, government ETS revenues are earmarked for climate activities. But programmes targeting emissions that are already covered by the ETS cannot reduce net emissions unless the government also reduces the number of credits that it auctions. And a strong majority of Kiwi economists agree that it is less costly to just reduce the ETS cap without implementing policies targeting emissions that are covered by the ETS.

The government could instead take the money it earns at ETS auction and return it to Kiwi households, to help them respond to rising energy costs. The payment to a family of four would be just over $1,000, at current carbon prices.

This kind of carbon dividend would be better than slush-fund expenditures like electric vehicle subsidies for helping mitigate any undesirable distributional effects of rising carbon prices.

It certainly would not solve all of the problems caused by high inflation and by a global oil shock. But it would help households start adjusting to higher longer-term energy costs. And it makes more sense than a temporary excise holiday.

Unfortunately, yesterday’s announcement also suggested that the government has a few other things planned for the money it earns at ETS auction.

At the same time, low-income households very likely bear a disproportionate burden from current petrol excise. A 1995 Toyota Estima does not impose any greater wear and tear on the road than a 2022 hybrid Toyota Rav-4 but pays an awful lot more to use the roads. Shifting petrol vehicles to road user charges would help undo a substantial inequity in the current road funding system and ease the burden facing households that have not yet been able to afford an upgrade.

Nothing can really cushion New Zealand from global oil price shocks. There were sensible approaches the government could have taken to ease some of the burdens. A temporary excise holiday is not one of them.