New Zealand generally likes arms control treaties.

I have a modest proposal for a disarmament treaty. Negotiations could start immediately. If we all disarmed, we would all be better off.

And now is exactly the time to do it.

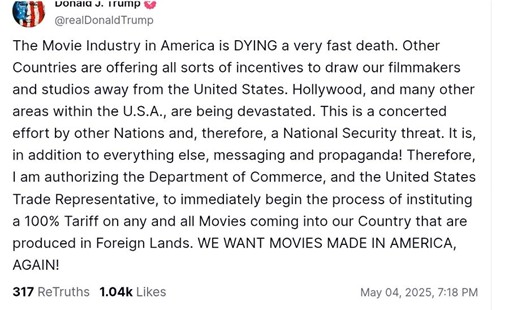

Yesterday, President Trump announced he would set 100% tariffs on “any and all Movies coming into our Country that are produced in Foreign Lands.” Why? “Other Countries are offering all sorts of incentives to draw our filmmakers and studios away from the United States.”

‘Reciprocal’ American tariffs on New Zealand goods and services, announced earlier this year, are nonsensical. New Zealand’s remaining tariffs are low. Particularly targeting New Zealand would make little sense.

But New Zealand, like other countries, competes to attract Hollywood productions by promising generous subsidies. Up to a quarter of an international film company’s spending in New Zealand turns into a ‘rebate’ from the government. The more they spend here, the more the government hands over as a subsidy.

It is a classic arms-race.

If every country could agree to stop subsidising film productions, Hollywood’s overall spending would decrease. No country’s industry would take a disproportionate hit.

But no country with substantial film subsidies wants to be first to disarm.

New Zealand’s film subsidies are large enough to regularly feature as a risk in Budget Economic and Fiscal Updates. Because total annual expenditure is not capped, costs can blow out. And while the Budget makes its best guess as to costs for the next couple of years, funding commitments stretch out over a much longer period.

America isn’t innocent. The state of Georgia provides a substantial tax credit for films produced in the state – as do California, New York, and others. Just watch to the end of the credits of a film to see whose taxpayers were on the hook.

And New Zealand is as guilty as all of them. Any tariff aimed at countries subsidising films will not miss the mark if aimed in our direction.

The American Department of Commerce will need to define what makes a film 'foreign' for tariff purposes. That is much harder than it sounds. And the President doesn’t seem likely to give officials a lot of time for fine crafting.

What makes a film foreign? Films are complex international productions. Scenes filmed in one country might be overlaid with actors filmed in another and CGI produced in a third. The financing could have come from anywhere.

It is terribly fraught. But there are a couple of relatively simple options. The kind of thing that a Department of Commerce could implement in a hurry.

And the simplest of the simplest options, which lines up entirely with the President’s claimed motivation, is to check whether a film received a foreign government subsidy.

Alternatively, the Department of Commerce could check a film’s audited production budget. If too much of that production budget was spent outside of the US, tariffs would apply.

Or, a two-part test could capture the President’s love of tariffs and his expressed displeasure with foreign subsidies. A movie could draw tariffs either if it had received any foreign subsidy, or if too much of its production budget was spent outside of America.

If America’s tariffs depend only on whether a large proportion of the film’s production costs were incurred outside of the United States, tariffs could have a particularly perverse outcome.

Any country might respond to this round of tariffs by increasing its existing film subsidies, trying to keep productions from shifting back to the United States. If one country does, other countries could easily follow. Countries failing to keep up will lose productions both to the United States and to the countries providing even higher subsidies.

The subsidy arms race then heats up rather than ending.

A disarmament treaty is the clearest path to ending the subsidy spiral."

No country would take a particular hit, but every country’s government could put the funding to more important purposes.

International film subsidies have always seemed like the kind of policy that countries would all wish to end, if they could all end them simultaneously.

Being the only country to end film subsidies would risk sharp reductions in your country’s film sector. But if everyone stopped subsidising films, the movie sector, internationally, would be smaller. No country would take a particular hit, but every country’s government could put the funding to more important purposes.

New Zealand has taken a leading role in shoring up support for free trade in response to recent American tariffs. It matters. Countries might otherwise be tempted to start setting tariffs not just on the United States in retaliation, but also on each other.

New Zealand could take the current round of film tariffs as impetus for film subsidy disarmament talks.

If the Americans set tariffs on films that have drawn foreign subsidies, agreement to end subsidies should be easier. Countries may wish to do it, even without multilateral agreement – making agreement easier.

If America’s tariffs instead depend on overseas production costs, the risk of subsidy escalation seems substantial. And the main winner of international film subsidy races is Hollywood.

There has not been a better time to start disarmament talks.

To read the full article on the Newsroom website, click here.